[ad_1]

Subjects

Twelve dancers (8 male, 4 female, age: 21.7 ± 3.6 years; height: 175.4 ± 10.2 cm; weight: 72.5 ± 10 kg) and ten non-dancers subjects forming a control group (6 male, 4 female, age: 21.6 ± 2.87 years; height: 174.4 ± 7.82 cm; weight: 66.1 ± 11.56 kg) participated in the study. To participate in the study, dancers were required to have a minimum of eight years of dance practice, while the potential effects of training level, age, and gender were not accounted for. Dancers were sourced from university-related dance groups, with a usual background of learning Hungarian Folk dance since childhood and maintaining consistent participation in practices and rehearsals. In the selection process, it was assumed essential that years of experience were necessary to learn folk dance properly. Given that many dance clubs maintain training standards comparable to those of professional dancers, the criteria for selection emphasized active membership in a folk dance ensemble and a substantial number of years dedicated to Hungarian folk dance. Non-dancer participants were selected based on the criterion that they had yet to engage in high-level sports previously, which could markedly influence their balance ability nor were they currently involved in such sports. Subjects in both groups were excluded if they had any musculoskeletal injuries or disorders that could affect balance or locomotion. All participants have given their written consent to take part in the experiment after they were informed about all aspects of it. The protocol was approved by the Science and Research Ethics Committee of the University of Physical Education, Hungary (TE-KEB/17/2021).

Dynamic balancing measurement

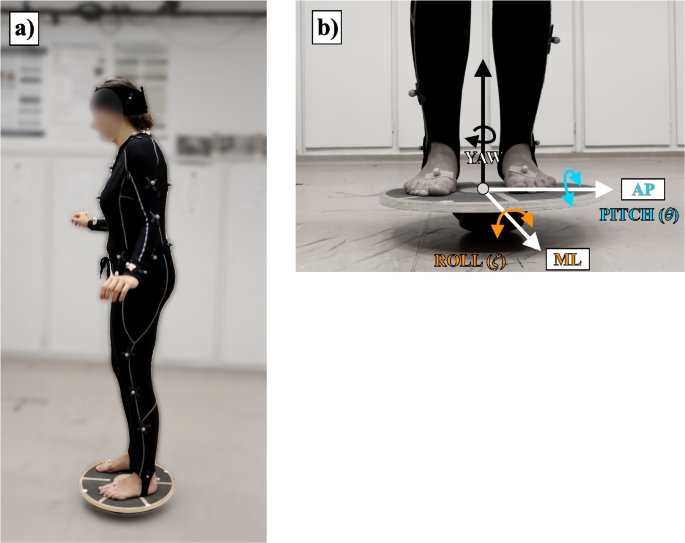

A dynamic balancing task or test is an experimental procedure designed to evaluate an individual’s ability to maintain balance when one or several types of external perturbation or dynamic conditions are imposed upon it [30, 31]. During the measurements, participants were exposed to continuous dynamic excitation. A balancing test on the unstable board was performed to efficiently measure how effectively one could maintain balance on an unstable surface [32]. For the measurements, a multiaxial unstable balance board (DOMYOS, DECATHLON; Villeneuve-d’Ascq, France) with a diameter of 40 cm was applied. Participants were instructed to stand on the unstable board with eyes open while maintaining a steady posture as still as possible (Fig. 1). Moreover, an OptiTrack (NaturalPoint Inc.; Corvallis, Oregon, USA) three-dimensional optical motion capture system was used to record the motion of the balancing devices as well as the movements of the participants. The motion was recorded using 18 infrared Flex 13 (OptiTrack, NaturalPoint; Corvallis, Oregon, USA) cameras and the Motive v1.10.3 software. The software is responsible for the cameras’ coordinates operation and recording the markers’ three-dimensional position. This measuring system has an accuracy of sub-millimeter (overall Mean 3D Error: 0.550 mm) [33], and the measurements were carried out with a sampling frequency of 120 Hz. Spherical markers (\(\varnothing\) 12.8 mm) covered with reflective coating were placed on the unstable balance board (five markers) to record its motion, whereas a full-body conventional marker-set was used consisting of 39 markers to capture the human motion [34]. The cameras cover a 4×2.5 m measuring area, with the unstable board in the middle.

Experimental protocol

The measurement tasks were introduced to the participants, and some additional time was given to become acquainted with the measurement device and the spinner (EDEA Skates; Crocetta del Montello, Italy). The spinner (or spin-trainer, a foot-sized plate with a curved contact surface with the ground) is an ice sport-related device used to imitate the rotary motion, inducing some disorientation in participants. For the spinning intervention, a movement that is common in Hungarian folk dance and could be performed by both groups was sought. Spinning around the horizontal axis is a recurrent motif in folk dance, so quasi-steady rotation in the absence of a partner was feasible using the spinner. Subsequently, participants were asked to fill out the Waterloo Footedness Questionnaire to determine their dominant leg (20 participants were found strongly right-side dominant, and two participants were slightly more left-side dominant) [35]. The protocol started with the base measurements (before spinning), a 60-second long bipedal balancing test on the balance board. Upon that participants engaged in rotational activity (spinning intervention) by performing ten complete one-foot upright spins using the spinner device while standing on their dominant leg. The rotational fatigue session typically lasted between 30 and 60 seconds. Following the spinning activity, the 60-second long balance measurement was repeated to assess the post-spinning effects (after spinning). During the pilot phase of the study, the spin number was determined as the point where subjects had experienced a partial loss of orientation, yet were still capable of returning to the measuring device and completing the measurement. Note that to eliminate the cross-over effect, a 10-minute long break was inserted in between the base measurement and the spinning intervention.

Data processing

The balance board has three degrees of freedom for rotation, which were consistently determined in relation to the subject’s position. Therefore, by utilizing anatomical markers on the participant, the balance board was rotated according to the anatomical planes in the AP (pitch), ML (roll), and frontal (yaw) directions (Fig. 1). Filtering positional marker data using a low-pass Butterworth filter (with a cut-off frequency of 5-6 Hz) has been a conventional approach in human gait analysis [36, 37]. Upon examination of our dataset, it was observed that smaller components contain valuable information beyond 6 Hz, and the signal is significantly distorted. Thus, our numerical data was processed using a fourth-order, low-pass Butterworth filter with a cut-off frequency of 15 Hz. To ensure consistency, the first and last five seconds of the 60-second trials were excluded from the analysis to eliminate any potential disturbances related to the balance board setup and landing. Moreover, due to the minimal friction between the ground and the bottom of the device, the rotational movement around the vertical axis (yaw) was found to be negligible during the measurements. Consequently, only the AP (pitch) and ML (roll) angles were considered for further analysis.

Two types of parameters were applied to characterize postural stability. The first type includes equilibrium parameters, which are directly associated with the stability of the balance board. These parameters are derived from the research conducted by Giboin et al., providing sensitive and reliable measures to describe the stability characteristics [38]. The equilibrium of the balance board (and therefore the subject) was defined by the parameters remaining inside the threshold zone. The threshold zone was calculated as the average value of rotation \(\pm 10 \%\) of the range of the rotation similarly to [38], with our method being more permissive as it allows board stability not just in the horizontal plane. Practically, this translates to a change of approximately ± 2\(^{\circ }\) from the average, considering a maximum deflection of around 20\(^{\circ }\) in both directions. From the 50-second measurement interval, the range of angles (RP for pitch and RR for roll) and the percentage of stable regions (SP for pitch and SR for roll) were determined, from which the ratio of stable regions (RSR)

$$\begin{aligned} {RSR} = \frac{{SR}}{{SP}}, \end{aligned}$$

(1)

and the ratio between the two angle ranges (RA)

$$\begin{aligned} {RA} = \frac{{RR}}{{RP}} \end{aligned}$$

(2)

could be calculated. Furthermore, the settling times for the first occasion (FSP for pitch and FSR for roll) were also determined, which refers to the duration when the angular movement remains within the stable zone for at least two seconds.

Moreover, our objective was to assess the complexity of postural control more directly. Traditional methods for quantifying postural control primarily rely on assessing the CoP variability; however, in recent years, the use of wearable sensors and motion capture systems has gained popularity as these methods allow for the evaluation of posture stability in three dimensions [22, 39]. In the present study, 3D marker data was utilized as an alternative to the CoP, to estimate the subjects’ center of mass (CoM). CoM estimation was carried out by calculating the geometric center of four markers positioned on the pelvic girdle (Left and Right Iliac Anterior Spine and Left and Right Iliac Posterior Spine). In terms of linear parameters: CoM path (\({P}_{CoM}\)) and area of the 95\(\%\) confidence ellipse (\({A}_{95\%, CoM}\)) were taking into consideration. According to Nagymate et al., the CoM path can be determined as at the length of total CoM trajectory during the measurement, whereas the confidence ellipse represents the smallest ellipse that covers 95\(\%\) of the points [40]. The area of the ellipse was calculated using the eigenvalues of the covariance matrix. Investigating the movement pattern more specifically, we extended our analysis beyond the CoM to include head movement. Head motion was evaluated using four markers strategically positioned on the head, with two markers placed in front and two at the back. Similar to the characterization of CoM, the path length (\({P}_{head}\)) and the area of the 95\(\%\) confidence ellipse (\({A}_{95\%, head}\)) was calculated for the head movement as well. This comprehensive examination gave us a detailed understanding of CoM and head movement patterns during the study. For the nonlinear analysis the calculated path lengths served as the basis. To gain a comprehensive understanding of the AP and ML movements, these components were examined individually during the analysis where two nonlinear indexes were chosen: sample entropy (SampEn) and fractal dimension (FD).

SampEn, is a valuable measure for evaluating the regularity of time-series data. It is calculated as the negative natural logarithm of the conditional probability that a dataset of length N, which has repeated itself within a tolerance r for m points, will also repeat itself for \(m + 1\) points without allowing self-matches [41, 42]. This measure plays a significant role in analyzing postural sway regularity and is used to determine the stability and predictability of movements [22, 43]. SampEn in our case was determined using the method available on the PhysioNet tool [44]. According to the literature, the values \(m=2\) and \(r=0.2\) were selected for the sample size of \(N=6000\) [22, 45].

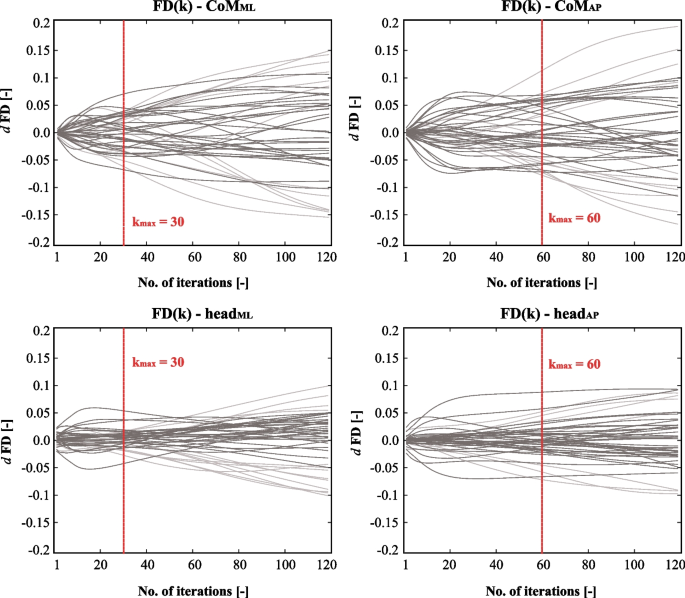

FD serves as a measure for assessing the complexity of the CoP signal and describing its shape. Several algorithms are currently employed to calculate fractal dimension, including the Higuchi algorithm [46], Maragos and Sun algorithm [47], Katz algorithm [48], Petrosian algorithm [49] or, the box-counting method [50]. This measure reveals the degree of self-similarity and intricacy present in physiological signals. For calculating the FD of CoM and head path lengths Higuchi’s algorithm was used. Higuchi’s method [46] is a widely applied time-domain technique to determine fractal properties of complex non-periodic, nonstationary physical data. The Higuchi’s FD depends on the length of the time series and an internal tuning factor \(k_{max}\). Higuchi’s original paper did not elaborate on the selection of the tuning factor, however, many examples can be found in previous articles [21, 51, 52]. Drawing from the work of Wanlissi et al., it is recommended to use a tuning factor within the range of \(10^1\) and \(10^2\) for a sample size of \(N=6000\) [53]. To determine the suitable \(k_{max}\) value, interpolation was conducted for each path trial for k ranging from 2 to 120. The difference between each interpolation point is depicted in Fig. 2. Based on the calculated results, \(k_{max}=30\) for the AP direction and \(k_{max}=60\) for the ML direction were selected. This decision was based on the observation that, for the vast majority of the time series, there were no significant changes in the FD values with respect to the subsequent iteration values.

Statistical analyses

Before the statistical analysis, the calculated variables underwent normality tests. The normality of distributions was assessed with the widely-used Jarque-Bera test (\(\alpha = 0.05\)), since it is a quite robust test for smaller sample sizes and for slightly skewed distributions [54]. More than 80\(\%\) of the balance board parameters successfully passed the normality test, however, only 15\(\%\) of the linear and nonlinear CoM parameters passed the test. As a result, parametric tests assuming a normal distribution were applied for the balance board parameters. Whereas, the CoM parameters, which mostly failed the normality test, exhibited a non-normal distribution, and only non-parametric tests could be used. A between study design was adopted to compare the control and dancer groups both before and after the spinning intervention. For the balance board parameters, a two-sample T-test was applied, while for the CoM parameters, a Mann-Whitney U-test was performed. A within-subject study design was adopted to test the effect of the spinning intervention. Wilcoxon’s signed-rank test was used to compare before and after trials for the CoM parameters, and a one-sample paired T-test was performed on the balance board parameters. The effect size was determined to assess the outcomes of the statistical tests in-depth. The method of calculating and interpreting effect size differs between parametric and non-parametric tests, as outlined in Table 1. All the statistical tests were conducted at a significance level of \(\alpha = 0.05\). All the statistical analysis were performed using the Statistics Toolbox of Matlab (version R2022b, The MathWorks Inc.; Natick, Massachusetts, USA).

[ad_2]

Source link